The ghosts that haunt Kayani

Somewhere around Nowshera, on the western edge of the GT Road before Peshawar, there is an unmarked exit to a town few have heard of. If taken, you will enjoy the road to Cherat, for it has two lanes, is remarkably well paved, and usually has very little traffic. Hamlets come and go, and as is typical of Pashtun enclaves, there are no women in sight. But before one reaches the foothills that rise up like a knife stuck in the base of the last plains of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, serving as a natural barrier between the ‘settled areas’ of that province and FATA, just prior to gaining altitude, the ruins of what was once an Afghan refugee camp engulf the road from both sides.

For some miles, this Moenjodaro of the Mujahideen insulates the trajectory to Cherat, perhaps as an architectural replication of the minds of the men you will meet when you arrive at the end of the road. And then, after climbing for almost an hour, in a terribly nauseating number 8 pattern, there comes a sign in big, block letters which says, “Welcome to Cherat: The Eagle’s Nest”. This is when you know you’ve arrived at the Headquarters of the Special Services Group of the Pakistan Army – the holy grail of this country’s elite special forces.

“The military is not committed to this conflict. But it’s not because of “strategic-depth” brinksmanship, nor the endgame “hedging” of the Haqqanis, not even due to India’s “Cold Start” doctrine. It is because it has serious emotional baggage”

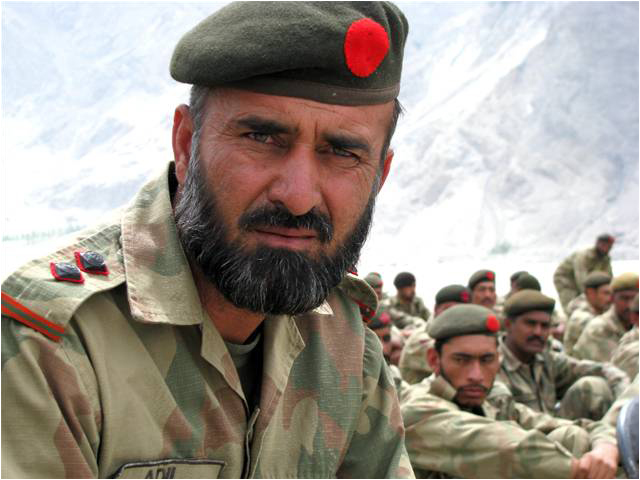

We’ve all heard of the SSG, the formation of crack commandos that evidently rescue hostages, vanquish hijackers, fast-rope into militant compounds, and generally look ominously menacing as they flank General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani when he’s out and about. Everyone remembers that it was the SSG’s Special Operations Task Force that had the final showdown at Lal Masjid, and how the same unit was later targeted by a suicide-bomber in a revenge attack in Tarbela. Frankly, some of these and other SSG war-stories are over-romanticised in our national narrative, especially by hawkish uber-jingoists, with the modern among this gang even resorting to putting up pictures and videos on Facebook, many featuring the SSG’s distinctive “Allah-Hu” march from the days when we actually used to have, and televise, military parades. Those days are gone, but the military folklore remains.

That’s absolutely fine. Even a state that is fundamentally flawed possesses the right to inflict nationalism upon itself, including the sort that features our uniformed praetorians. And in times of war, such hyper-patriotism can be welcomingly stirred into the undercooked omelette of militarised morale to make sure the latter appears well done, even if it isn’t.

So let the hawks romanticise the SSG. Or the rest of the Army. Or the Rangers or the Levies or the FC or even the Coast Guards. It really doesn’t matter, for the Pakistani military does not want to fight this war.

That’s right. It’s not news that the military is not committed to this conflict. But it’s not because of “strategic-depth” brinksmanship, nor the endgame “hedging” of the Haqqanis, not even due to India’s “Cold Start” doctrine. No, those are official reasons for public consumption and posturing diplomacy. They’re good enough motives to influence the Pakistani military’s strategic calculus, at least from its own perspective. But still, all of them are constructed and contrived reasons, conceived by khaki strategists to convince themselves, as well as others, about how things really ought to be. Thus, these are talk-show reasons. Or drawing-room reasons. Or conference-hall reasons. Not intrinsic ones.

The ‘real’ types of reasons – especially in paranoid, semi-failed and irrational security states – that drive or mitigate war are, always, intuitive and emotional. And the Pakistani army has serious emotional baggage when it comes to fighting this war, for it is evident all over Cherat.

It is in that remote mountainous cantonment where one glimpses the slivers of this Army’s confused raison d’etre: A sign that points to the direction of Srinagar as well as Jerusalem; a memorial dedicated to the war-dead from 1965, embarrassingly smaller than the one dedicated to 1971; Coats of Arms of various Raj-era units, that once conquered and killed locals here, chiselled along the face of the mountains; and of course, emblazoned quotes from the Quran. And then, at the far edge of the camp, past a 30-foot mural of an SSG warrior who is declaring in Farsi,“Mun Janbaz Um” (that he is ready to give up his life), there is the Officer’s Mess: A single-story structure with a view more befitting of a millionaire’s Swiss chalet than the haunt of men who command an elite, third-world military formation.

But once inside, along the walls of the main hall, all you see are the ghosts of battles past.

This army was never ready for counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations before it jumped into them, because deployment in that type of combat requires small, dynamic formations that can think independently and “on their feet”

Photographs, of each and every SSG officer killed in action, adorn the rich teak panelling. The pictures go around the room, about the size of any upper-class Pakistani foyer, covering almost three of the four walls. A few of the images, from the early wars, are black and white. The rest of them, from newer, more familiar conflicts, are in colour. Among the artificial swords, antique rifles, and a cheap oil landscape of Shaitan Taikri (a jagged outpost in the Ali-Barangsa sector on the Line of Actual Control in Siachen) there are a whole lot more of these fresh, framed fatalities.

Image analysts would have a field day in this SSG shrine. Some of the officers lost in earlier battles are clean-shaven, with a debonair and dapper English country-gentleman look to them. Then come the moustaches of the ’70s. Then the beards of the Siachen era. But then, a notable pattern begins. Younger officers. Older officers. Lots of them. All killed in the War on Terror. Very, very recently.

In his phantom punching that aimed at preempting the Clinton visit’s agenda, General Kayani said many things in his GHQ meeting with our parliamentarians last week. He postured: “They [the US] will have to think ten times [before attacking] because Pakistan is not Iraq or Afghanistan”. He bluffed: “If anyone convinces me that everything will be sorted out if we act in North Waziristan, I will take immediate action”. He even got to play statesman-in-chief: “For short-term gains, we cannot lose [sight of] our long-term interests [in Afghanistan]”.

But then, the general appealed.

Citing a staggering statistic, Gen Kayani let us into what’s really beginning to haunt his institution: That the army has suffered 12,829 casualties since 2001, including 3,097 killed, with what the New York Times reports as an “unusually high ratio of one officer killed for every 16 soldiers since it [the Pakistan army] began fighting the Taliban”.

This is critical. Like him or not, agree with him or not, but if you just believe Gen Kayani’s math, then it means the Pakistan Army has lost almost 194 officers in this conflict. As the average strength of a Pakistani infantry battalion (primarily the type of unit deployed in forward areas and that most prone to casualties) is about 900 men, with around 10 or so of them being officers, then Kayani’s accounting means his army has lost enough enlisted men to completely wipe out more than three entire battalions (that’s one brigade) and incapacitate 14 or so battalions (almost 5 brigades). But the real problem is that the army has lost enough officers to decapitate around 20 battalions; a shocking, disturbing statistic, especially for an institution that has been documented to be thoroughly weaved together through fraternal, kinship, tribal and legacy connections, and where the officer calls all the shots – on and off the field.

If they have weren’t already been briefed by Munter’s defence analysts about this on their trip, then Clinton, Petraeus, Dempsey et al should think hard what they dealing with. Sure, the intransigence to not commit to combat from the Pakistan Army has many ‘larger’ reasons, but the root cause may well be morale – the toughest factor to quantify for battle – or lack of it.

In an elitist army where many officers are related to each other, and where the commander-centric modules of conventional training ensure that units are highly dependent on officers to lead them, it’s a safe bet to assume two things: One, that almost all of Pakistan’s top brass have lost an officer they know and/or are related to, or work directly with someone in uniform who has. And two, that Pakistan’s undertrained and underequipped soldiers are increasingly leaderless in battle.

After due sympathies and respect for such a tremendous loss, it must be stressed that this is the Army’s own fault. The policy decision to commit troops in FATA etc has been debated too often, so let it be a forgone conclusion that the Pervez Musharraf/ Ehsan-ul-Haq/ Ashfaq Kayani/ Nadeem Taj/ Shuja Pasha-led GHQ-ISI combine made some questionable strategic and operational decisions in the last decade.

Just focus on what really went wrong in FATA operations for the army: a top-heavy institution that has for decades trained for conventional war with India, expecting its officers to mostly lead all formations – small and large – into battle, and thus (much like it’s colonial-era predecessor) heavily invested in the “thinking and doing” capacity of its officers versus just the “doing” potential of its soldiers.

That is where the army’s extraordinarily high officer-to-soldier losses have come in. This army was never ready for counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations before it jumped into them, for deployment in that type of combat requires small, dynamic formations that can think independently and “on their feet”. As our enlisted men have always been treated for the initiative-lacking, “Allah-u-Akbar” swearing, soldiers that they essentially are, the need to achieve viable objectives has forced the army to thrust its officers to over-commit in frontline deployments they’ve never trained for either. As more of these ranks have been killed – over-exposed by ‘leading from the front’ operations and/or increasingly ‘target killed’ by selective snipers – internally, for the Army’s officer corps, this means more brothers, cousins, nephews and in-laws are also dead.

So, for the Pakistan Army, this war is questionable. Not just strategically. Nor economically. Not even religiously. But more than any other reason, existentially. Thus, the SSG warrior’s mural in Cherat lied: He might be ready to give life in battle…But he doesn’t really want to fight this war.